Archiving and referencing the Apollo source code

It was fifty years ago, July 20th 1969. Six hundred million people all over the world were holding their breath watching on television the blurry black and white images of the first manned spacecraft landing on the moon: I was one of them, and I will never forget the huge emotion we all felt.

Software was a pillar of the Apollo mission …

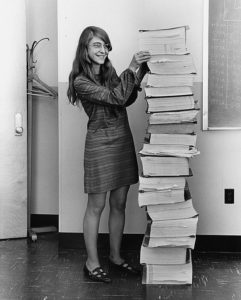

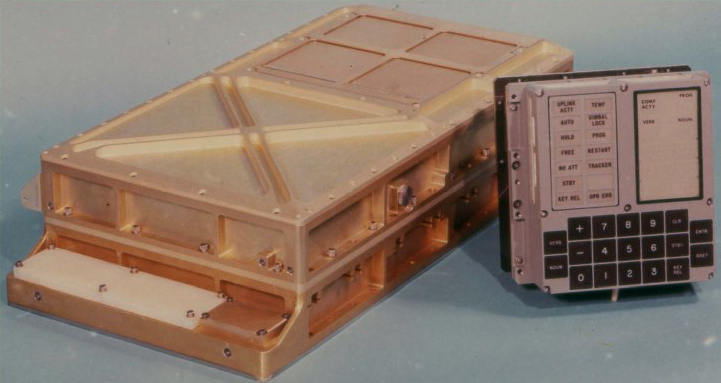

Back then, very few people knew that a key role in that landmark achievement was played by software, run on the Apollo Guidance Computer, also known as AGC, developed by a great team at MIT led by Margaret Hamilton. And yet, just minutes before the landing, several program alarms, 1201 and 1202, signalled a computer overload that could have jeopardized the entire mission, if they had not been properly handled by the system. We can now read a breathtaking account of these events by Don Eyles, one of the engineers that wrote the code, published a recent book, and is also featured in the beautiful Hack the Moon website.

… and we have full access to it

Today, we have the great chance to be able to explore the 60.000 lines of this source code, thanks to

- Ron Burkey, who got the idea to recover the source code of the AGC back in 2003 while watching the movie Apollo 13, and never stopped working on this

project ever since, retyping code from the scans of the code printouts from the MIT Museum, and now hosted at the Internet Archive, and producing in particular an amazing simulator of the AGC that can be used to run the software and play with it; that code has been later uploaded on GitHub by Chris Garry, making it easy to look at it and propose fixes - and the fact that in the United States software developed under federal funding is actually in the public domain: a simple and great idea that still needs to make it in old Europe.

As the AGC was programmed in assembler, which is far from being very human readable, the source code is full of detailed comments that provide us a sort of full immersion in the mind of the developer culture back in the 1960s, and it is great to see how many people have started delving into it.

Archiving and referencing landmark source code for the long term

Here at Software Heritage we are delighted to be able to contribute to this effort, by archiving for the long term the software source code of the AGC, and by providing a means to reference specific fragments of the code that is designed to stand the test of time, using persistent intrinsic identifiers (see also the full paper describing them) also known as SWH-IDs.

Here are a few fragments of the AGC source code that I am particularly fond of, together with their persistent intrinsic identifiers. Try clicking on the text in these fragments: you’ll be brought to the Software Heritage archive and you’ll see them in context.

Burn, baby, burn!

In the program for the Lunar Module, one routine called BURNBABY was in charge of powering on and off the main propulsor for five different LEM programs. Each program was implemented as a call to BURNBABY with a pointer to a table of parameters.

Here is a great fragment from the comments, that has the SWH-ID

Here the complete identifier with context (repository and lines of code): swh:1:cnt:665f8e95921e92776819b719f780ddbece2b78ac;lines=62-81;https://github.com/virtualagc/virtualagc/

# THE MASTER IGNITION ROUTINE IS DESIGNED FOR USE BY THE FOLLOWING LEM PROGRAMS: P12, P40, P42, P61, P63. # IT PERFORMS ALL FUNCTIONS IMMEDIATELY ASSOCIATED WITH APS OR DPS IGNITION: IN PARTICULAR, EVERYTHING LYING # BETWEEN THE PRE-IGNITION TIME CHECK -- ARE WE WITHIN 45 SECONDS OF TIG? -- AND TIG + 26 SECONDS, WHEN DPS # PROGRAMS THROTTLE UP. # # VARIATIONS AMONG PROGRAMS ARE ACCOMODATED BY MEANS OF TABLES CONTAINING CONSTANTS (FOR AVEGEXIT, FOR # WAITLIST, FOR PINBALL) AND TCF INSTRUCTIONS. USERS PLACE THE ADRES OF THE HEAD OF THE APPROPRIATE TABLE # (OF P61TABLE FOR P61LM, FOR EXAMPLE) IN ERASABLE REGISTER 'WHICH' (E4). THE IGNITION ROUTINE THEN INDEXES BY # WHICH TO OBTAIN OR EXECUTE THE PROPER TABLE ENTRY. THE IGNITION ROUTINE IS INITIATED BY A TCF BURNBABY, # THROUGH BANKJUMP IF NECESSARY. THERE IS NO RETURN. # # THE MASTER IGNITION ROUTINE WAS CONCEIVED AND EXECUTED, AND (NOTA BENE) IS MAINTAINED BY ADLER AND EYLES. # # HONI SOIT QUI MAL Y PENSE # # **************************************** # TABLES FOR THE IGNITION ROUTINE # **************************************** # # NOLI SE TANGERE

Here honi soit qui mal y pense seems to hint that the incredible feat of programming the AGC was not fully recognised at that time, and I would add here that we still have way to go to see great research software taken into account in academic careers.

Then the authors even resort to Latin to stress the criticality of the tables of parameters (“noli se tangere” means “do not touch”).

And by the way, here is why the routine is called BURNBABY.

The silly thing and the wizard

In the lunar landing phase, the AGC asks the astronaut to turn the LEM (the “silly thing”) around, so that the landing radar can be initialised. Just to be on the safe side, the programmers added a double check, jumping back at the beginning of the routine where the position is verified (that’s the “see if he’s lying in the code below”), and then of course, we go to see the wizard… BURNBABY.

Note for geeks: if you want to understand the calling convention, and the two different return addresses corresponding to TERMINATE and PROCEED below, you should have a look here.

CAF CODE500 # ASTRONAUT: PLEASE CRANK THE TC BANKCALL # SILLY THING AROUND CADR GOPERF1 TCF GOTOPOOH # TERMINATE TCF P63SPOT3 # PROCEED SEE IF HE'S LYING P63SPOT4 TC BANKCALL # ENTER INITIALIZE LANDING RADAR CADR SETPOS1 TC POSTJUMP # OFF TO SEE THE WIZARD ... CADR BURNBABY

Software Heritage: a special place for software source code

It is great to be able to pinpoint like this precise fragments of code in a blog post, an article, a tweet, or a documentation, and indeed many collaborative software development platforms offer this functionality. But development platforms are not archives: sometimes they go away, like Gitorious, Google Code or CodePlex, and often the code they store can be altered, or moved around: this may lead to link rot if you use them to write blog posts like this. Indeed, this is what already happened to the great 2016 article by Quartz, with many of its links into GitHub now dead (see for example here, here and here).

What makes Software Heritage really special, and set it apart from other platforms, is that it has been designed precisely to avoid all this:

- it is an archive: this means that everything you find in it now will

still be there tomorrow, and your work describing a landmark piece of software will still be relevant in a few years; - it offers intrinsic persistent identifiers: this means that you can refer to code fragments independently of the platform on which the code was originally hosted, and the version control system used.

We are delighted to support and preserve for the long term the efforts that passionate people make to delve into landmark software source code, exploring its contents and sharing their findings.

Interested in taking the dive? The field is yours!

Roberto Di Cosmo, Director of Software Heritage