Why the space age’s most epic code still matters

It’s 2003. You’re watching “Apollo 13,” and you’re struck by a wild, almost insane idea: what if you could run the actual flight software that guided humanity to the moon? That was Ron Burkey. His singular obsession launched The Virtual AGC Project, a digital archaeology mission to rescue the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) code from the brink of obscurity. Fast-forward two decades, and his tireless work—painstakingly retyping code from a tower of faded printouts—has given us a time machine.

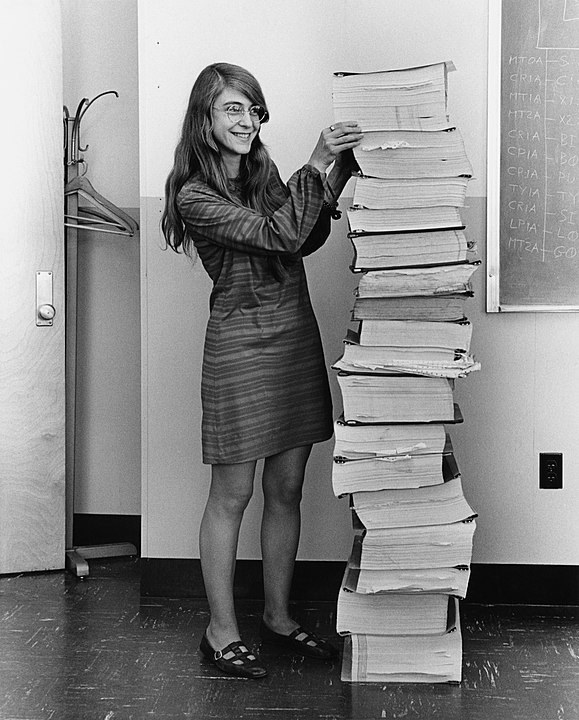

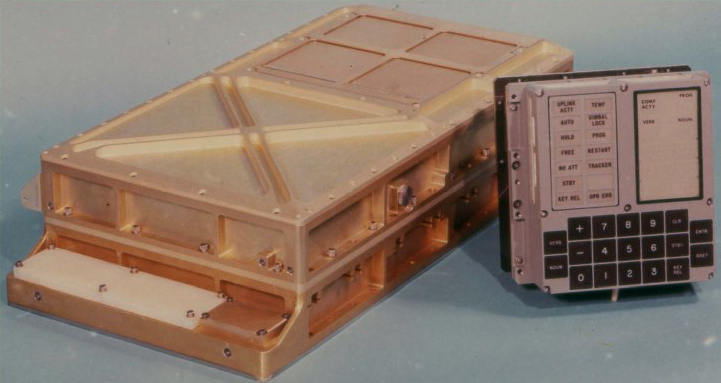

This isn’t just about nostalgia. It’s about a 60,000-line codebase that is, by every measure, a masterpiece of engineering under impossible constraints. As Burkey noted, the AGC was “very slow and had a very small memory,” yet it ran “real-time multitasking fault-tolerant executive software… quite sophisticated given the limited Hardware resources.” This code is a direct line to the minds of the people who worked for Margaret Hamilton, the visionary who led the software team.

From paper to pixels: A digital dig

The journey of this code is a story in itself. It didn’t just exist on a hard drive somewhere; it was a physical artifact: “a stack of 11-inch by 14-inch fan-fold paper a couple of inches thick.” The challenge wasn’t just to scan it—it was to make it usable.

Burkey’s team discovered early on that modern OCR (Optical Character Recognition) was useless. As he famously put it, “OCR is no CR.” The faded, low-quality printouts from the 1960s were a non-starter. Instead, a heroic team of volunteers manually transcribed every line of code. They’d then use modern assemblers to re-create the executable and compare it to the original, correcting any discrepancies until the transcription was perfect. This meticulous process even used clever visual tricks, overlaying colorized text on scans to spot potential errors.

This grueling work isn’t just about accuracy; it’s a testament to the code’s inherent value. It’s why non-profits like Software Heritage are so dedicated to its preservation. Burkey’s insights were part of a talk at Software Heritage Preservation (SWHAP) Days in Paris.

The universal archive and the value of saved code

So what’s the ultimate destination for this salvaged code? It’s not just gathering dust in a closet or on a few random GitHub repos. Software Heritage houses all of it in a global, non-profit archive. Think of it as the Library of Congress for all publicly available source code. The archive isn’t just storing files, but creating persistent intrinsic identifiers (SWHIDs) for every piece of code, right down to specific lines. This means that a researcher can cite a single line from the Apollo code today, and that link will still be valid decades from now.

You can browse the entire Apollo codebase, a truly immersive experience that allows you to explore the very software that navigated the mission.

This raises a crucial question: beyond the historical thrill, why does this matter?

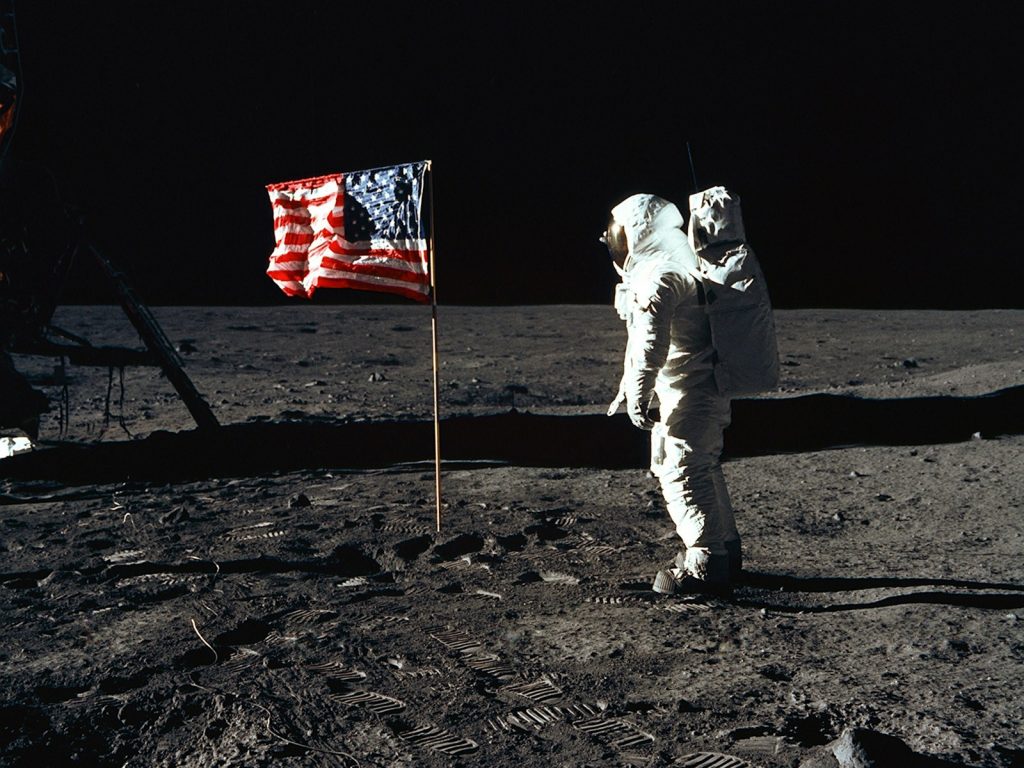

The code itself is a primary source document, a window into the mind of developer culture back in the 1960s. The comments, often a mix of technical notes and subtle human personality, provide context that textbooks can’t. Take, for example, the program called “Burn, Baby, Burn,” which was tasked with igniting the lunar module’s descent engine. The name traces back to the Los Angeles riots of 1965, inspired by the phrase used by disc jockey extraordinaire Magnificent Montague when spinning the hottest new records. It’s a testament to the code’s ability to capture not just technical notes, but the cultural zeitgeist of the era. The codebase is also a master class in efficiency, a reminder of how elegant and resourceful software can be when constrained by minimal hardware.

Finally, the very existence of this archive is a win for the concept of open knowledge. The fact that software developed with federal funding is in the public domain in the United States is a “simple and great idea” that still needs to be adopted globally. The preservation of the AGC code is a powerful argument for why we should treat software not just as a tool, but as a vital part of our cultural and intellectual heritage.

The Apollo code is just one example of this vital heritage. To build a comprehensive record of all software, we need everyone’s help.

Check the Archive to see if your code is already preserved for posterity; if not, add it with our Save Code Now feature.