Meet the conservator fighting digital decay

Digital art is fragile. Its medium is code, and code decays. This is the reality Nika Maltar faced when she started her FOSS journey with a nonprofit focused on preserving digital-native internet art. Her work centered on testing open-source tools and frameworks—the kind that grab a website and create a permanent, interactive copy. That experience was a realization that community-driven tools aren’t just useful, they’re essential for keeping software-based art from vanishing.

It can be easy to overlook the physical objects that hold our digital past. A 5.25-inch floppy disk might seem like a relic, but what if it contains the source code for the first commercially successful independent video game from a country?

At the Technisches Museum Wien (TMW), this isn’t a hypothetical. It’s the starting point of a critical preservation project focused on the 1989 video game “Der verlassene Planet,” (The Abandoned Planet) a text-and graphics-based adventure game developed by Hannes Seifert for the Commodore 64. This perspective highlights code’s role as a human document, not just machine instructions.

This type of mission drives people like Nika Maltar, a digital conservator. Her work at a nonprofit like Rhizome showed her how open-source tools and community involvement are essential for the long-term preservation of software-based art. The Technisches Museum Wien is on the same page: its software collection and technical tools are intended to be non-commercial and, whenever possible, operate with open technologies. The physical object can last, but the data—the real value—is trapped, and it’s a race against time to save it.

Maltar’s mission to preserve software began in 2019, while she was studying Conservation of New Media and Digital Information. It wasn’t a lecture, but a single paper in a seminar on source code documentation that changed everything. The work, titled “Software Heritage: Why and How to Preserve Software Source Code,” presented a radical idea: that the world’s code could and should be saved as a public resource for all time.

That moment was the spark. Now, Maltar is not just a student of that mission, but a part of it, joining the ranks of Software Heritage Ambassadors.

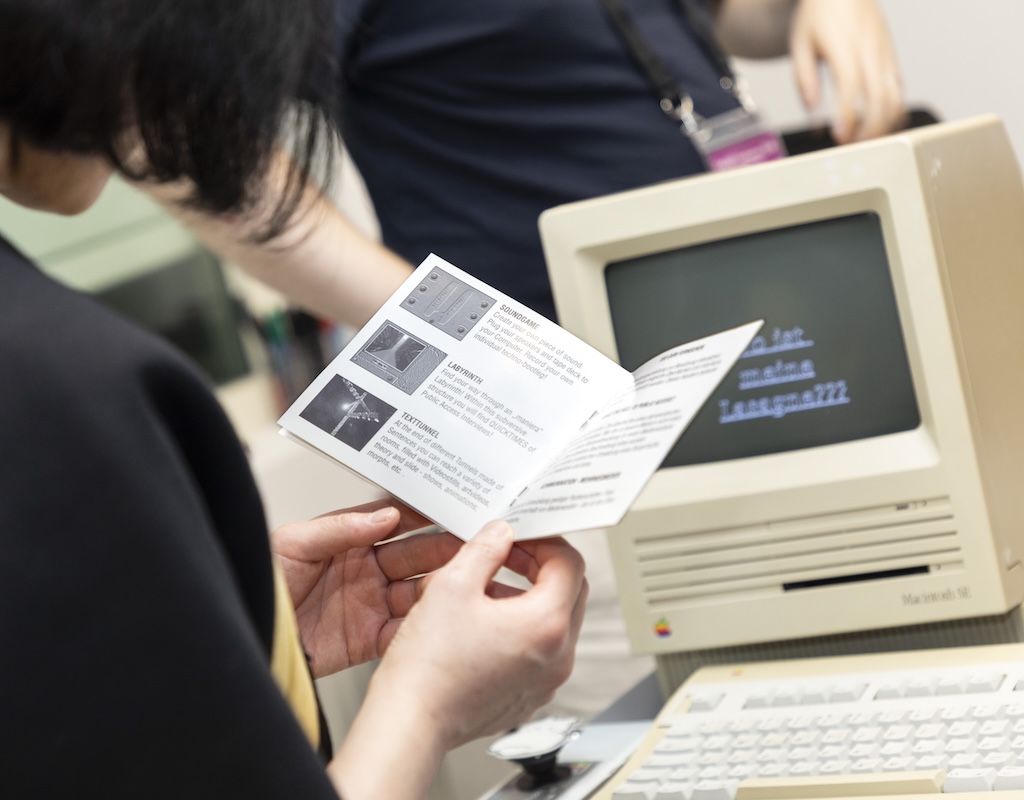

Since December 2021, Maltar has been coordinating the Department for Software Collection and Preservation at the Technisches Museum Wien. Under Maltar’s coordination, the department has undertaken several significant projects that reflect this shared mission. In 20212, the First Software Archive and Collection Department was launched as part of the Research Institute. This initiative, co-developed with Martina Griesser-Stermscheg, has already led to the collection of approximately 30 unique software objects and the extraction of over 200 software elements from existing physical collections. That same year, Maltar also co-developed the softwareLAB. This infrastructure for extracting software from obsolete carriers and born-digital formats has enabled archiving approximately 200 software objects, forming the TMW Software Archive. TMW conducts ongoing research on topics like graphics card emulation and builds emulation environments with partners Rhizome, aBITpreservation, and OpenSLX.

In 2023, Maltar also co-developed a project titled The Codebreakers and contributed as a co-principal investigator. The project centered on how people use and assess digital infrastructure in their daily lives. The project’s goal was to create a new, interdisciplinary approach that allowed researchers to do two things: document contemporary user experiences and develop new methods to preserve and run commercial and proprietary software in a museum setting. This work was a way to ensure that these digital objects could be authentically interpreted and used as they were originally intended. For Maltar, it all comes back to a core belief: that software is a vital part of our lives. A key aspect of Maltar’s work at TMW is community-oriented preservation. Maltar has co-developed a participatory collecting approach, a new form of collecting where the museum deliberately surrenders its traditional institutional prerogative of interpretation to interested communities, making them key players in the institutional production of knowledge right from the start. This strategy involves conducting oral history series and preservation performance interviews to document intellectual property rights, technical specifications, and development histories. This information is crucial for reconstructing software environments and ensuring long-term access and functionality.

As a Software Heritage Ambassador, Maltar’s primary goal is to integrate the SoftWare Acquisition Process (SWHAP) into TMW’s source code acquisition workflows. The SWHAP has been developed by the Software Heritage team in collaboration with the University of Pisa, with support from UNESCO. The ultimate goal is to make the source code and documentation accessible through multiple channels, including a GitHub repository, the TMW’s database, a custom MediaWiki page, and the Software Heritage universal archive. This practical work will serve as a model for other cultural and educational institutions seeking to engage with software preservation.

Software Heritage Ambassadors are volunteers who offer expert advice in various sectors and languages on how to use our services. Here’s more information on how to book one for a free consultation.

If you’d like to connect with Nika Maltar, you’ll find contact information on her Ambassador profile.

We’re also seeking passionate individuals and organizations to volunteer as ambassadors and help grow the Software Heritage community. If you’re interested in becoming an Ambassador, please share a bit about yourself and your connection to the Software Heritage mission.

Featured image photo credit: Martina Fließer

Copyright: Technisches Museum Wien mit Österreichischer Mediathek, September 2024