Open source and the European skills gap

A lot of conversations about Europe’s tech future focus on a familiar problem: the skills shortage. The continent’s top developers are increasingly mobile, leaving for other regions with more integrated tech ecosystems and deeper pockets. It’s a real challenge for competitiveness, and it’s one that a recent white paper about the role of open source in Europe from the Eclipse Foundation tackles head-on.

Experts from organizations like the OSI, OECD, Gaia-X, and Open Forum Europe collectively address topics ranging from EU sovereignty and competitiveness, artificial intelligence (AI), to new regulations on hardware and geopolitical tensions.

Software Heritage Director Roberto Di Cosmo contributed a section to this paper that makes a powerful case for a simple, yet often overlooked solution to the talent gap issue: open source. His message is clear: open source can be the key to addressing this shortage by creating an ecosystem where developers and researchers can not only stay but also thrive and build their expertise right where they are.

The open source advantage for a talent crunch

Unlike proprietary systems, which keep their cards close to the chest, open source offers a fundamentally different way to learn. It allows developers, engineers, and researchers to freely access, experiment with, and contribute to cutting-edge technologies. This isn’t theoretical knowledge; it’s real-world, hands-on experience that builds a stronger, more resilient local workforce. Instead of losing our best minds to other shores, we can give them the tools to build something great at home.

The elephant in the room: AI and traceability

The conversation around skills isn’t just about quantity; it’s also about what skills will matter next. This is where artificial intelligence comes into play. AI-powered code assistants are already changing the game, promising to reduce development time and lower the barrier to entry for new languages. However, this shift brings its own set of challenges.

First, new skills are required to manage and optimize this new kind of AI-assisted development. We’re moving from just coding to also directing and refining what a machine produces. Second, the sheer volume of software that needs maintenance will increase dramatically. More code, more problems—unless we have a robust way to handle it.

And perhaps most importantly, there is a serious risk of losing traceability in software origins. When AI tools are creating code, it can be harder to track where every line came from—a huge red flag for security and compliance. In an era where AI is generating vast quantities of new code, the work of Software Heritage becomes even more crucial by offering a canonical, tamper-proof record of code history—an indispensable foundation for transparency, reproducibility, and trust. It’s an infrastructure for trust.

Inspired by distributed software development practices, Software Heritage introduced its “Software Heritage Identifier” nearly a decade ago, now tracking over 50 billion artifacts. Rebranded as the Software Hash Identifier (SWHID), it’s now a globally recognized, community-driven standard for universal adoption across archives, regulations, research, and industry. The SWHID was officially published as the ISO/IEC international standard 18670 in April 2025.

The quip from a Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, that “kids shouldn’t learn to code; they should leave it up to AI,” might spark debate, but it underscores a critical point: the nature of software education has to adapt. The goal of Software Heritage is to ensure that, as the landscape changes, we don’t lose the fundamental skills of software creation and management—or the ability to know where our code came from.

Academia’s pivotal role and the need for recognition

It’s easy to think of tech as purely a private sector game, but academia has always been a driving force behind open source. From university labs to open collaborations, countless foundational projects have come from scholars. A survey on research software highlights some striking findings:

- 50% of research software is over nine years old, showing its enduring value.

- 62% has an impact beyond academia, proving it’s not just for the ivory tower.

- The vast majority is FOSS, and only 10% is proprietary.

These numbers highlight the importance of keeping research software maintained and updated. They also point to a crucial problem: recognition. A national plan for open science argues that software production should be recognized in research careers, ensuring that researchers get proper credit for their contributions. Yet, the integration of open source into academic evaluation and funding remains a significant challenge. By providing proper incentives, we can turn a valuable but often-overlooked activity into a wellspring of innovation.

The fourth sector and a regulatory blind spot

The white paper introduces the concept of a “fourth sector” or “meshed society.” This new model of decentralized, community-driven initiatives like open source needs to be considered by regulators. The challenge is that current EU regulatory frameworks, like the Cyber Resilience Act and AI Act, are often designed for the traditional corporate model of companies producing goods for consumers. This can create compliance burdens for open source communities that aren’t built to handle them. The paper argues the open-source community needs to work with policymakers to ensure regulation doesn’t accidentally stifle innovation.

A geopolitical tool for tech sovereignty

Beyond just talent and innovation, the paper frames open source as a geopolitical tool for shifting power away from a few dominant players toward a more distributed ecosystem. It argues that Europe should use open source to reduce its reliance on non-European tech providers. The EU’s approach to digital sovereignty contrasts with the U.S.’s focus on supply chain security and China’s state-led, top-down approach. The paper asserts that open source and permissive licensing models often benefit challengers, and Europe must leverage this to strengthen its digital resilience.

Open source software comprises nearly 80% of all software. In Europe, it contributes between €65 and €95 billion to the EU’s GDP.

A coordinated effort for a resilient future

The vision for a sustainable open source ecosystem requires more than just a good idea; it needs a plan. Di Cosmo’s contribution outlines a coordinated effort across three key areas:

- Policy: Integrate open source better into open science initiatives and make funding as straightforward as it is for proprietary software.

- Education: Step up open source training at all levels, preparing developers for new regulations and teaching them how to use AI coding tools while maintaining core skills.

- Infrastructure: Establish a global, universal software archive for preservation, reference, and integrity—exactly what Software Heritage provides. We need improved traceability and large-scale collaborative tools for code analysis and sharing.

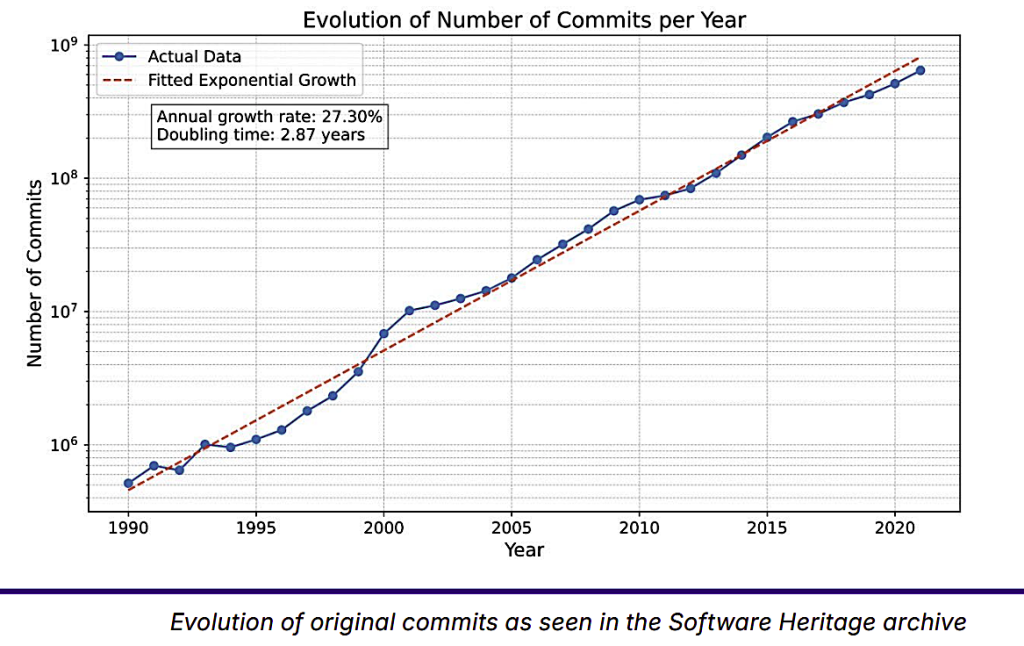

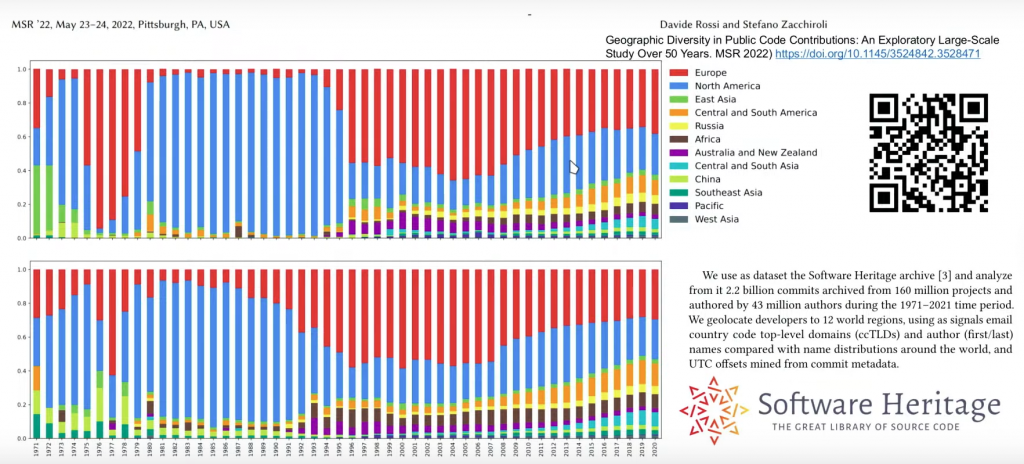

This vision is built on the reality that software development is inherently international. A study on geographic diversity in public code contributions highlights just how global open source projects are. Our mission at Software Heritage is to preserve and catalogue these contributions for future generations, creating a shared resource for humanity’s digital knowledge.

In the end, open source is more than just a tool. It’s a catalyst for training, a driver of talent retention, and a foundation for a more resilient digital future. By working together and building solid, lasting infrastructure, we can tackle the skills gap and keep tech and science moving forward for years ahead.