Open Science needs a software revolution: Here’s a blueprint

Open Science, built on the principle of making research transparent and accessible, is powered by an infrastructure of shared knowledge. This ecosystem includes not only open data and open access to publications, but also the fundamental software that enables modern research.

Despite significant progress in sharing papers and datasets, software—the very engine of scientific discovery—remains an often-unrecognized and unpreserved part of the scientific record. This creates a critical gap in our ability to reproduce and build upon research.

The Software Heritage Open Science Strategic Blueprint, available on Zenodo, is a new manifesto that addresses this challenge. It argues that we must treat code not just as a tool, but as an essential and permanent part of our intellectual heritage, ensuring its preservation and accessibility for future generations.

It argues that we must treat code not just as a tool, but as an essential and permanent part of our intellectual heritage, ensuring its preservation and accessibility for future generations.

Authored by a team of experts, it outlines a grand vision for closing this gap, directly aligned with the mission of Software Heritage: to collect, preserve, and share all publicly available source code as a common good for research and society. It’s about building a shared infrastructure that serves all disciplines, from physics to the humanities, ensuring that the embedded knowledge in every line of code is never lost.

The strategy: From awareness to adoption

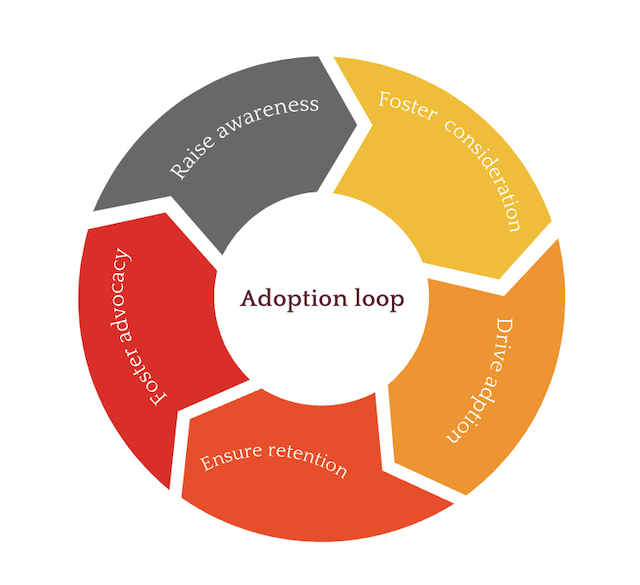

It’s not just a wish list but a strategic plan to shift how academia views and treats software. The authors draw on Brian Nosek’s strategy for scientific reform, outlining an “adoption loop” that moves from raising awareness to driving concrete adoption. It’s a pragmatic, multi-level approach that targets everything from individual researchers to national and international funding bodies.

The strategy acknowledges that different stakeholders have varying motivations and goals. For researchers, it’s about making it easy to get credit for developed software and to verify or reproduce results. For institutions, it’s about providing the tools to track software contributions and produce metrics for evaluation. For infrastructure, it’s about connecting to the Software Heritage archive and ensuring an interoperable ecosystem.

Key to this mission is a set of products and tools that make it simple to engage with the archive. The blueprint highlights the SoftWare Hash Identifier (SWHID), a persistent identifier for code that just became an ISO standard. There’s also the BibLaTeX @software package and a new citation feature to simplify citing code, as well as the CodeMeta standard to ensure consistent metadata. These aren’t just technical specs; they’re the building blocks for a new scholarly ecosystem where software is a first-class output, just like a journal article or a dataset

Building the network, facing the challenges

A mission this ambitious can’t be achieved alone. The blueprint details a network of stakeholders, engaged in the academic sector, from funders like the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, which supports the recently announced OSPO-RADAR project, to mirror partners that host full copies of the archive, like ENEA, GRNET and Unidue. It’s also powered by a community of Ambassadors, a diverse group of research software engineers, data analysts, and librarians who are on the front lines, running training sessions and advocating for the cause. The goal is to create a “train the trainer” model to scale this effort globally.

The blueprint is also clear-eyed about the challenges ahead. These are not trivial problems, but the plan addresses them directly.

The report outlines five key areas:

- Landscape challenges: The uneven adoption of Open Science and the fragmented nature of scholarly infrastructures.

- Sustainability challenges: The need to secure long-term funding and expand the global network of mirrors.

- Product challenges: Ensuring that crucial tools like the SWHID and CodeMeta are not just maintained but widely adopted.

- Communication challenges: Tailoring the message for a diverse range of audiences, from policymakers to PhD students.

- Awareness challenges: The simple fact that many researchers still don’t know why or how they should be preserving their code.

These are significant hurdles, but the blueprint lays out a clear plan to overcome them, with specific strategic responses and metrics for measuring success. This is a comprehensive roadmap for making software a recognized pillar of Open Science. It’s a call to action for everyone in the research community—from the person writing a single script to the institution shaping policy—to ensure that our digital heritage is preserved for generations to come.

You can read the full 21-page blueprint, “The Software Heritage Open Science strategic blueprint for academia,” on Zenodo.

Our community powers our work. Join the effort by becoming an Ambassador, joining one of the Open Science membership programs, or joining the science community.